- July 14, 2025

How architecture and urban design can transform our approach to the homelessness crisis by creating therapeutic and inclusive environments

Across Canada, emergency shelters are showing concerning occupancy rates: 85% on average, with peaks reaching 106% during the coldest nights. An estimated 35,000 people across the country are without shelter each night. These figures, revealed by recent national counts, reflect a reality that frontline workers know intimately: our current support systems are overwhelmed.

The urgency of addressing the homelessness crisis demands that we rethink our care and living environments. This raises a crucial question for us as designers: how can architecture support a continuum of services adapted to the non-linear journeys of people experiencing homelessness? And even more: can built environments become transition catalysts, capable of reconciling urgent intervention with the need for sustainable support?

To deepen, or even attempt to resolve, such questions, it’s important to integrate diverse perspectives into the discussion. By bringing together viewpoints from architecture, urban planning, public safety, and social intervention, a shared observation emerges: beyond their undeniable necessity, traditional solutions are no longer sufficient. It has become urgent to recognize that the built environment can either aggravate exclusion or become a powerful lever for personal and social reconstruction.

Integrative architecture: when space welcomes

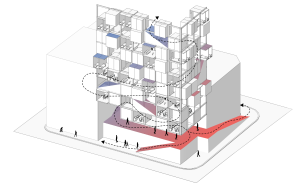

At the heart of our approach lies the conviction that architecture must respond, through design solutions, to the needs of the people for whom it’s intended—in this case, we think of the fluctuating needs of individuals and intervention teams, which will guide us toward integrative architecture with flexible and modular spaces.

This architecture begins with a deeply human approach, based on listening and co-creation with the people concerned and the resources working in the field. The field approach indeed reveals complex realities that statistics cannot capture, as Émilie Fortier from Mission Old Brewery emphasizes: “One of the first things that can help generate solutions is for professionals to leave their offices and come to where people experiencing homelessness are, to familiarize themselves with the issues as they’re lived daily.”

Understanding the realities of homelessness, particularly among youth where interpersonal problems constitute the primary cause of housing loss, reveals the crucial importance of creating environments that foster the reconstruction of social bonds. When more than half of homeless youth cite family conflicts as a trigger, this reveals deep relational wounds. The response cannot be limited to emergency housing: it must include creating therapeutic spaces that enable rebuilding trust and social connections.

This participatory method allows us to move beyond preconceived ideas to understand real needs. Designing inclusively will involve, for example, considering:

The typology of spaces: their orientation and visual openings; the natural light they welcome or the isolation they allow

The typology of spaces: their orientation and visual openings; the natural light they welcome or the isolation they allow

- The chronotopy of uses and places—that is, the different uses that the same space can accommodate throughout the hours of the day

- A configuration of common spaces that fosters social interactions

- Materials: conveying human warmth or institutional coldness

- The fluidity of spaces, which benefit from facilitating progressive transitions from emergency to reintegration

This evolutionary approach resonates with the vision of Antoine Buisseret, Partner and Design Director at Lemay: “The notion of design process is very important. We benefit from embracing the concept of unfinished design: conceiving projects that offer opportunities to evolve over time. We’ll develop solutions with field actors.”

Prioritizing the right options becomes possible by mobilizing all the communities involved in a context that allows them to fully express their reality—a context where authentic and sustainable solutions can naturally emerge.

Creating spaces of transition and diversity

Innovation lies in creating environments that accompany journeys rather than dictating them: if the traditional shelter system is focused on control, it results in a difficult intervention context. On the contrary, the expressed need is to support the transition from the street to sustainable housing solutions, particularly for people dealing with addiction and mental health issues.

For these individuals, access to a continuum of services can be complex, as these are too often scattered, making support pathways laborious for people who are already vulnerable. Integration into “territories of care” opens the way to more coherent ecosystems, where emergency housing, health services, and social support naturally coexist in a caring environment.

The design of the surroundings of these service points will also be critical, as Émilie Fortier emphasizes: “To welcome people who aren’t ready to go inside… How do I ensure it’s not the sidewalk that’s used, but rather the interior of our property, for example? Design can help us find solutions that will facilitate coexistence.”

Design laboratories have enabled such transition spaces toward reception structures, opportunity spaces that can take various forms while offering secure outdoor spaces, designed as natural extensions of resources. These are respite zones integrated into the urban fabric that offer coolness, human connection, and dignity.

The goal is, therefore, to create spatial sequences that respect each person’s rhythm: more protected spaces for those who need security, semi-public zones to facilitate progressive reappropriation of social life, interfaces with the community to foster inclusion. In other words, services helping homeless individuals can open onto their neighbourhood, become intergenerational meeting places, host community activities that benefit everyone. This sequential approach allows for gently accompanying the transition between isolation and social reintegration, combining vulnerability, security, dignity, and the right to public space.

Reimagining inclusive public spaces

Too often, public spaces follow a barely disguised logic of exclusion: anti-sleeping benches, minimal lighting, absence of basic amenities. This defensive approach solves nothing: it merely displaces problems while impoverishing the urban experience for the entire community. What can we integrate into our designs to better protect, support, and welcome a diversity of populations, including people experiencing homelessness?

Too often, public spaces follow a barely disguised logic of exclusion: anti-sleeping benches, minimal lighting, absence of basic amenities. This defensive approach solves nothing: it merely displaces problems while impoverishing the urban experience for the entire community. What can we integrate into our designs to better protect, support, and welcome a diversity of populations, including people experiencing homelessness?

The expertise of Laurent Dyke, Strategic Advisor—Homelessness and LGBTQ2+ Issues at SPVM, offers valuable perspective on what should be prioritized in development regarding security: “Places that will be problematic are often somewhat enclosed places, with a roof, some depth, and where it’s dark.” This observation underscores the importance of designing open and well-lit spaces. “Design can help us in this regard: well-lit places, wide places, with two access doors—for intervention, it’s always better, it gives us the latitude to intervene in a secure context for everyone.”

We also want to design truly welcoming public spaces where security stems from diversity of uses rather than systematic exclusion. This might involve adding certain services near a park or subway entrance to make the place more pleasant to frequent for the entire population. This pragmatic approach responds to the fundamental needs identified by Émilie Fortier: “Often, when people experiencing homelessness settle in an entrance, it’s to sleep, urinate, and maybe eat: we’re really talking about basic needs. If these needs find answers in the neighbourhood, we’ve really reduced many situations that hinder coexistence.”

A call to action

This transformation cannot be the work of a single discipline. “The first step is being aware of our biases, also aware of our clients’ biases and the mandates we receive,” emphasizes Audrey Girard, Partner and Director of Urban Design and Planning at Lemay. “Then, in the process, it’s about reaching out to people who have field knowledge, knowledge complementary to ours, and staying open to opportunities.”

This collaborative approach reveals concrete opportunities to seize. Laurent Dyke shares the inspiring example deployed in the Skid Row neighbourhood in Los Angeles: “The City, in association with a community service, had organized storage for people experiencing homelessness. They mobilized a warehouse and installed recycling bins inside: a homeless person can access it and store their things there, then access them in relative privacy.” This simple but effective solution illustrates how space can respond to fundamental needs while preserving dignity.

We are convinced: homelessness is not inevitable. It’s a planning challenge we can meet together, by designing spaces that accompany reconstruction rather than consolidate exclusion. Together, let’s activate the power of design to create more humane cities.

To deepen these reflections, discover our Care+Design approach and explore our other analyses on therapeutic architecture and creating inclusive urban spaces.