We often say what we do in business “keeps the lights on”. We’re often talking about how lighting is a basic sign of life for the places we work and create, but we need think beyond that baseline. There’s more to it than just flipping a switch.

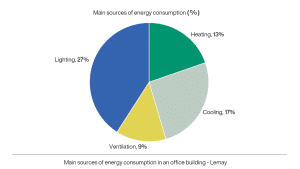

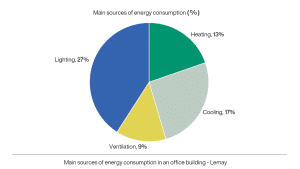

When it comes to Canada’s total energy demands, buildings account for over 40%. From our homes to our workplaces, lighting forms a major part of our energy consumption—in office buildings alone, it can take up more juice than heating, cooling, or ventilation. That’s a lot, and if we’re going to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions for a more sustainable future, it means that lighting’s energy efficiency needs to be improved.

Reducing the energy needs of lighting

Enter the largest source of lighting you can find: Natural light. From the development of new spaces to the retrofitting of preexisting ones, living environments that are designed to be infused with natural light can considerably reduce the energy needs of a building.

We’ve seen it whenever we’ve put our NET POSITIVETM tools into practice, including our own workspaces: When it comes to sustainability initiatives, what’s good for the planet is also good for us. Natural light in buildings benefits those who use that building, helping to set biological clocks and balance our circadian rhythms.

The benefits of sunlight in the workplace

It’s all part of putting biophilic design into practice, where our emotions and well-being are improved through natural elements being integrated into the spaces we inhabit. The presence of the sun alone improves moods, raises morale and productivity, lowers fatigue, and contributes to a general sense of satisfaction someone can have with a space. Research has shown the harm that’s caused by low natural light levels, ranging from visual fatigue, headaches, and stress to lowered concentration, demotivation, and even depression.

That makes the measurement and comparison of a space’s amount of natural light to its consumption of artificial lighting crucial to the design process. Doing so can help plan for the optimal fenestration ratio—the arrangement of windows and doors on a building—of a structure, as well as the selection of glazing and shading systems like solar blankets or brise-soleil.

Even if natural lighting and complementing blackout systems aren’t feasible, lighting remains an essential facet of design because the quality of light matters. Attention to detail helps to determine the intensity or colour rendering ability of artificial light used in a space, or even how circadian lighting can be used to replicate the natural light spectrum, all to avoid harshly and improperly lit environments.

Our living environments can only benefit from designs that let the light in.

Take a look at some examples of how the biophilic design of space highlights the benefits of nature by improving our well-being.